From the Philippines: Civil War Show and Tell

by Lee McKenna

In the centre of the large room, there is a small table, draped in the colourful weaves of the east Pacific. A Bible is open and a candle is lit. Amidst the folds of the cloth is the image of a woman, carved of dark brown Acacia from here, the Philippine Island of Panay. She is kneeling, her lower body wrapped in the indigenous skirts of the Visayas. Her hands cover her eyes, perhaps in tears, perhaps in prayer. Her naked breasts lie atop the protruding belly of an expectant mother. Though I have given her an African name – Emzarah, meaning Mother of all life, she is from here. And this is a group in labour.

The participants in this training of trainers in conflict transformation and peacemaking each bring their stories of civil conflict into this seaside compound for mutual show-&-tell, shared learnings, the acquisition of new skills and the creation of new networks of support. The combination of cultures, language and story – from Northeast India, Myanmar, Sri Lanka, the Philippines (from Mindanao to Luzon) and Canada – creates a unique recipe for powerful exchange – greater than the sum of our parts!

The Philippine hosts tell of a history of dynastic – movie-star, even – politics, resource depletion, ‘land-grabbing’, displacement due to militarisation and resource extraction, the export of mostly Filipinas, through human trafficking and OFW (Overseas Filipino Workers) programmes, disappearances, extrajudicial killings of activists, journalists and political opponents – as well as those conflicts closer to home that create opportunities within movements for creativity and change.

The sea is only metres away, rambunctious in typhoon season, providing a white-capped backdrop to the local town’s festive annual celebrations of their patron saint. Arevalo, situated at the south-west corner of the Island of Panay in the province of Iloilo, is typically Filipino, its streets congested with the colourful public transit vehicles known as jeepneys, this country's version of the three-wheeled tuk-tuks, and pedestrians who calmly weave their way through it all, part of the unseen set of rules that manage a chaos that is only apparent, not real. Inside, we recall the basics of popular education, born here and in Latin America, elicitive, experiential, disruptive, discomfitting – and life-changing. We play games that help us to get to know one another, level any perceived or unseen hierarchies and begin to break down the barriers of anxiety with the stranger, the unfamiliar and the unknown. Typical Philippine exuberance is tempered by the reserve of their Asian neighbours; initial aversion to a style of learning so distinct from the lecture model so well inculcated by colonial masters gives way eventually to a bond forged in fun and mutual vulnerability.

On the first day we talk about what we want to learn – and the modest list on the flipchart grows to include a longer list of specific hopes and expectations. This group is serious, wants to see change, wants to be change.

For the Sri Lankans, the peace gained with the government troops’ 2008 massacre of the leadership of the LTTE, is fragile, the government’s offering of its success as a model for other countries dealing with insurgencies – ‘terrorists’ they call them, borrowing the now-convenient language of the ‘global war on terror’ – while the international community mulls its indictment before the International Criminal Court on charges of war crimes and genocide against the Tamil minority. For the Burmese, the much-celebrated conversion of its government from SLORC (State Law and Order Restoration Council) to SPDC (State Peace and Development Council) to open-to-the-world democracy is partial, at best. Yangon, the capital, displays little of the in-your-face violent excesses of the early years – following theannulment of the 1990 election results that saw the National League for Democracy (NLD) win 81% of the Parliamentary seats; the NLD’s leader, Aung San Suu Kyi, enjoys a freedom denied her over 15 years of house arrest and an international red carpet of acclaim. Yet northern-most Kachin State remains in the grip of violent civil war, peace talks with the new reformist government having broken down over Kachin demands for autonomy within a federated Burma and their opposition to the government’s approval of Chinese hydro-electric projects. Seventy-thousand Kachin have been internally displaced; another 10,000 have fled over the Chinese border. As well, 90,000 stateless Rohingya Muslims have fled the western coastal state of Rakhine following clashes with Rakhine Buddhists that seem to give credibility to reports of a disturbing policy of government-backed segregation, contrasting starkly with the democratic reforms Myanmar's leadership has promised the world since half a century of military rule ended last year.

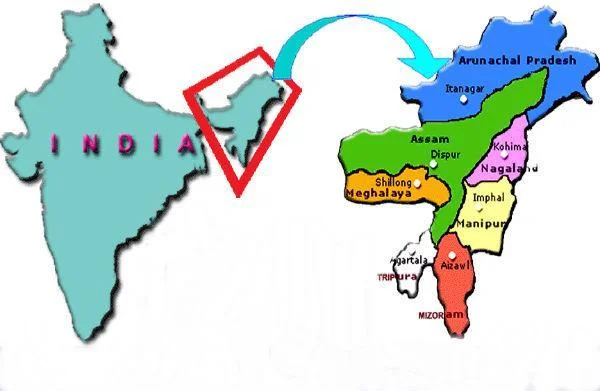

Northeast India is geographically odd, jutting deep into China/South Tibet and Myanmar, almost surrounding Bangladesh to the south, with Nepal and Bhutan perched at the ‘Chicken Neck’ or Siliguri Corridor that connects the North-east with the body of India. It is also home to the world’s longest-running – though perhaps least known – civil conflict. With the departure of the British Raj, the new Indian government reneged on its promise of self-determination for the Naga people. Odd for reasons beyond geography, the Naga are 90% Christian and, of those, 90% are Baptist, harvest of a 19th century evangelism project whose enduring impact reaches deep into Myanmar, home to the second largest Baptist denomination in the world.

Since the mid-1990s, the Baptist Peace Fellowship of North America has been working to mediate amongst the five groups that splintered over the years from the original nationalist movement – and with some remarkable success – contributing to a 1997 ceasefire. After 14 years of negotiations between the Indian government and insurgency leaders, a non-territorial agreement was reached, creating a pan-Naga supra-state body which will have legal authority over cultural, developmental and social rights of the Nagas living across several states in the Northeast. The following month, inter-ethnic conflict broke out between the largely Christian Garos and Hindu Rabhas, the latter complaining about the increasingly aggressive proselytising of the Christians.

As we listen to one another’s stories, we note the similarities between our respective situations of conflict and the distinctives of each – the common threads of resource extraction, poverty, corruption, betrayal, displacement, violence and land-grabbing cloaked in religion, tribe, history or politics. The stories reverberate across the room, questions fly. In the day’s closing ritual we acknowledge the common humanity that underlies our conflicts, our violence, our fears and hatreds. And we acknowledge Emzarah – emblematic of our labour, hopes for peace and the wisdom to make it happen gestating within.

Lee McKenna is a trainer, teacher, writer, facilitator, musician and storyteller with more than 20 years of experience working in Conflict Transformation. Her areas of expertise include non-violence, economics, human rights, ethics, public policy, anthropology and theology. Lee is highly recognized as a Peacemaker and in 2010 was awarded the YMCA Peace Medallion. She holds a MDiv degree and is a PhD candidate at the University of Toronto.